It seems to be a frequent concern amongst suburban dwellers, particularly due to the rise in extreme weather and high winds in Ireland.

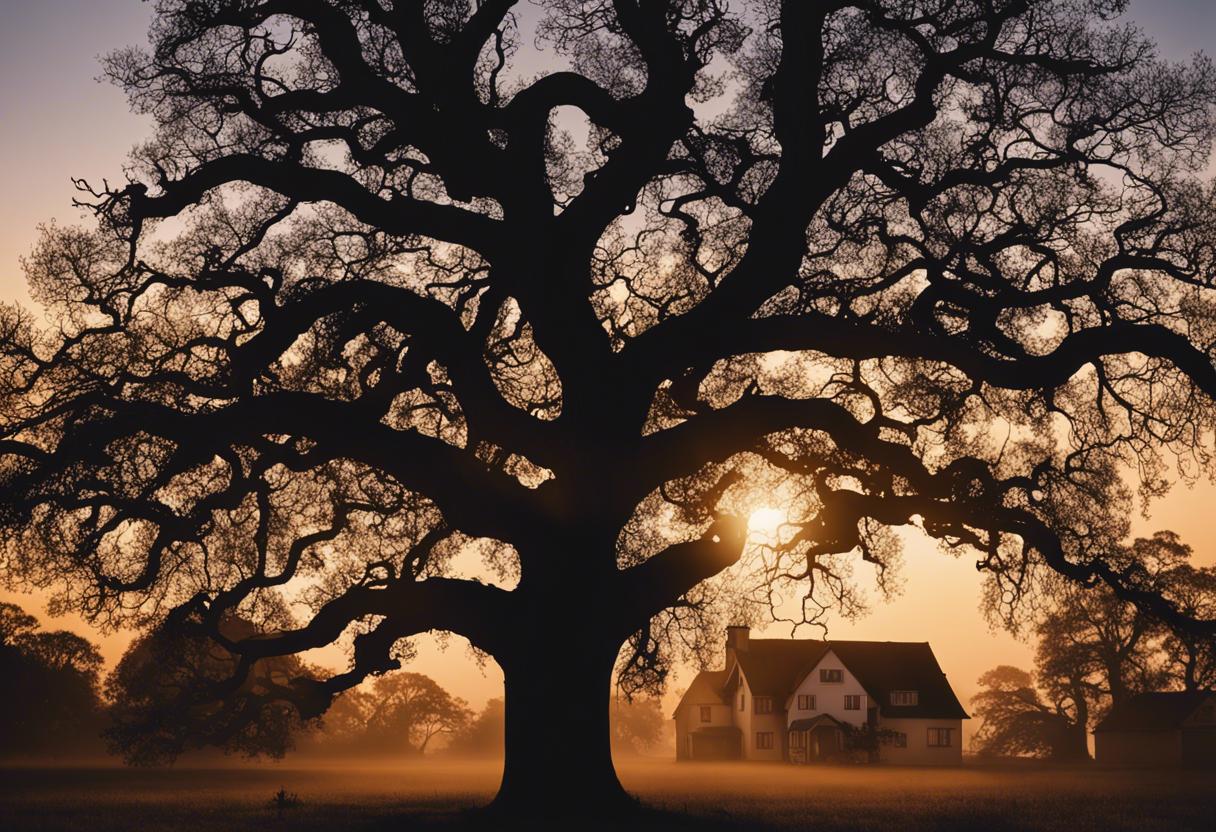

The issue revolves around our neighbour’s ageing oak tree, one with many feeble twigs on the fringes. It’s perched precariously against our shared boundary wall, with a significant chunk of it looming over our backyard. Despite spending €500 two years ago to trim it back as per our rights, we continue to grapple with the fallout of numerous heavy and potentially hazardous branches.

A pertinent example was an incident today where one such branch dropped directly onto our outdoor furniture and children’s toy tractor, while the little ones were fortunately on the other end of the garden. The thought of the damage it could have done if they had been there at that time, chills me.

Isn’t it the responsibility of our neighbours to look after their threateningly old oak tree that seems to be a potential risk?

Considering the burden of storage or central heating – which costs more to shift to an air-to-water pump system? Is it prudent to sell our current home before we procure the new, smaller one? When I’m no longer around, would my daughter be required to pay inheritance tax if she decides to sell my property?

Crucially, we need to know our rights and what our neighbour’s obligations are in terms of reducing the tree substantially to its sturdier branches to avert any foreseeable danger. Since I’m told that I’ve no right to further prune it, nor do I wish to carry the financial burden once more, shouldn’t they be accountable for their tree’s upkeep?

Any guidance on this matter would be greatly appreciated.

The perils of huge trees too close to homes, whether due to potential for injury or damage from strong gusts during storms, or hindrance to solar panels due to reduced sunlight, cannot be undermined.

In your scenario, because the contentious tree resides on your neighbour’s land, your options are limited. Despite the onus being on your neighbours to ensure their tree doesn’t pose a danger to anyone, getting them to adhere can be quite challenging in some cases. Regrettably, there is a dearth of laws regarding dangerous trees in Ireland, unlike in England and Wales.

To address the issue at hand, it’s crucial to rely on your neighbour’s level of understanding and willingness to cooperate. Your first step should be to approach them, expressing your worries about the potential harm their tree might cause and suggesting they consider minimising its height. This initial contact is aimed at letting them know about the related risks and your concerns.

Try to avoid compelling them into immediate action if you notice any signs of resistance. Instead, invite your neighbour to have a look at the issue from your viewpoint, in your garden. Ask them to acknowledge your fears and propose a potential resolution. This procedure might require some patience and time but it’s up to you to convince them of splitting the cost related to adjusting the tree’s height.

Should this method prove unproductive, consider taking a legal path. For that, you’ll need to meticulously document every falling branches instance, take photos of the tree and its branches, damage (if any), the distance from the boundary, as well as note down the dates and all communications with your neighbour.

It is mandatory to have detailed incident logs to create a persuasive argument. Your most potent weapon when your neighbour denies cooperation is a works order issued by the District Court under Sections 43 to 47 of the Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act, 2009. Additionally, hiring a tree specialist to examine the tree from your garden and draft a brief report on the risks of falling branches and a possible solution is recommended. This report combined with the evidence collected will be assessed by your solicitor to determine the strength of your case in order to convince the District Court to approve your works order for height reduction.

The Act covers a broad variety of elements on or near the boundary. If the court believes that the oak tree forms part of the general boundary because of its impact and closeness, and your evidence of risk and damage is convincing, it might contemplate issuing a works order. If the work is evidently beneficial for both sides, the Act offers provisions for cost division. Your solicitor will provide advice on these facets of the 2009 Act.

Patrick Shine is a recognised civil engineer, a geomatics surveying professional, and a member of the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland.

Looking for answers to any questions? Feel free to drop a mail at [email protected]. Please remember, the information shared in the Property Clinic column is purely for knowledge enhancement purposes and is not meant to be relied upon for personal decisions. Seek professional or expert counsel prior to making or avoiding any choices based on this information.